Human emigration, the act of relocating from one place to another, has been a defining force in both human evolution and societal advancement, as noted by Yuval Noah Harari. Kerala, with its long history of movement both within India and overseas, offers a vivid illustration of this phenomenon. Over centuries, the patterns of migration from Kerala have shifted significantly, with the profiles of migrants and their chosen destinations evolving in response to changing economic, social, and global contexts. In 2011, John Samuel conceptualized these shifts as distinct “waves” of emigration, identifying five such waves up to that point. Today, Kerala is witnessing a sixth wave, marked by a surge in students pursuing higher education at foreign universities, reflecting the state’s ongoing and dynamic engagement with global migration trends.

Nearly half of all households in Kerala have at least one member who has emigrated. Each of these emigrants can relate to one of the six distinct waves of migration.

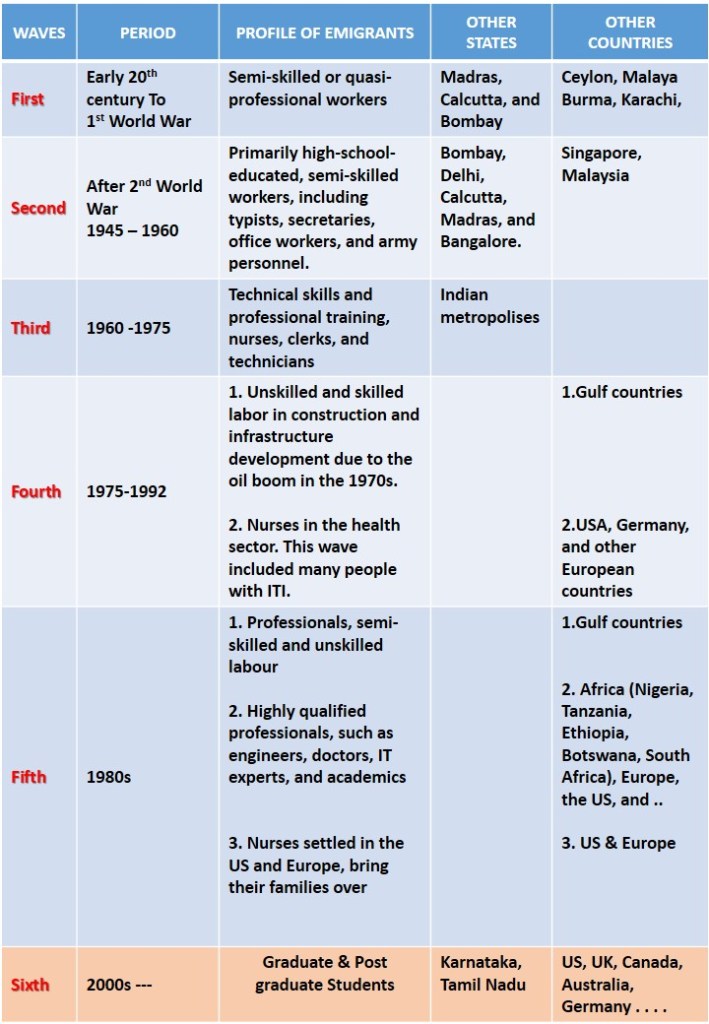

The first wave of migration from Kerala, which took place in the early 20th century, was marked by the movement of semi-skilled and quasi-professional workers to a range of destinations, including Ceylon, parts of Malaya—primarily for plantation work—Burma, and major Indian cities such as Madras, Calcutta, Karachi, and Bombay. This migration was largely driven by the search for better employment opportunities and was concentrated in specific regions of Kerala, such as Palghat, central Travancore, parts of Malabar, and Kochi. This wave of outward movement is believed to have continued until the onset of the First World War, setting the stage for subsequent patterns of migration from the state.

The second wave of migration from Kerala unfolded in the period following the Second World War, roughly between 1945 and 1960. During these years, a significant number of Keralites moved to destinations such as Singapore and Malaysia, as well as to major Indian cities including Bombay, Delhi, Calcutta, Madras, and Bangalore. Unlike the earlier wave, which consisted of semi-skilled or quasi-professional workers, this phase was marked by the migration of individuals who were primarily high-school-educated and semi-skilled. The typical occupations of these migrants included typists, secretaries, office workers, and army personnel. This shift reflected both the growing educational attainment in Kerala and the changing nature of employment opportunities available in urban centers and overseas. The movement was also influenced by the social and economic transformations occurring in Kerala at the time, as well as the demand for clerical and administrative skills in expanding metropolitan economies and colonial outposts in Southeast Asia.

The third wave of migration from Kerala, which occurred between 1960 and 1975, marked a significant shift in both the profile of migrants and their destinations. Unlike earlier waves that were dominated by semi-skilled or clerical workers, this period saw a growing number of individuals with technical skills and professional training seeking opportunities elsewhere. The migrants of this era included technology professionals, nurses, clerks, and technicians—reflecting the increasing emphasis on education and specialized training in Kerala during the post-independence years.

Most of these migrants moved to major Indian metropolises such as Bombay, Delhi, Calcutta, Madras, and Bangalore, where rapid industrialization and urban expansion had created a strong demand for skilled workers. Nurses from Kerala, in particular, became highly sought after in hospitals across India due to their reputation for competence and dedication. Similarly, technicians and technology professionals found employment in the burgeoning public and private sector industries, while clerks filled essential administrative roles in both government and corporate offices.

The fourth wave of migration from Kerala, spanning from 1975 to 1992 (up to the Kuwait War), marked a period of unprecedented mass emigration, fundamentally reshaping the state’s economy and society. This wave had two principal destinations. The first was the Gulf region, where the oil boom of the 1970s triggered a surge in demand for both unskilled and skilled labor, especially in construction and infrastructure development. Large numbers of Keralites, including those with ITI (Industrial Training Institute) qualifications and technical skills, migrated to countries such as Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates, Kuwait, and other Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) states. By the early 1990s, the estimated number of Kerala migrants in the Gulf exceeded 640,000, with the total Indian migrant population in West Asia reaching several million.

The second major destination comprised the USA, Germany, and other European countries, where the growing need for healthcare professionals—particularly nurses—opened new avenues for migration. Kerala’s well-established nursing education system enabled thousands of trained nurses to secure employment in hospitals and care facilities across the West, especially during periods of acute staff shortages. This migration of skilled healthcare workers was often facilitated by professional networks and recruitment agencies, and it contributed to Kerala’s reputation as a source of high-quality nursing talent.

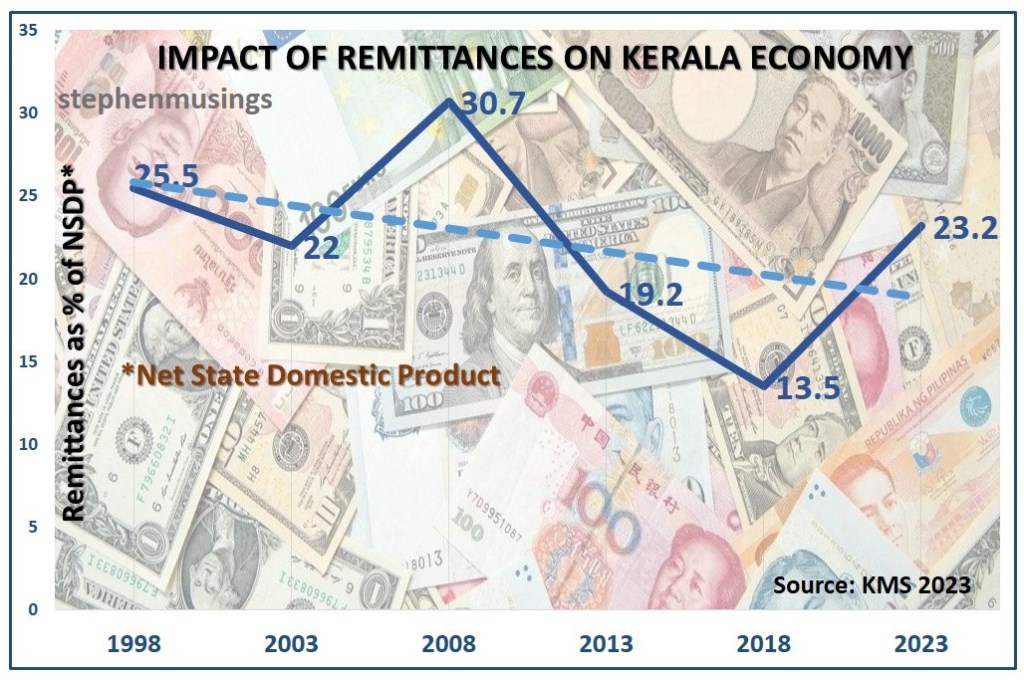

The economic impact of this wave was profound. Remittances from migrants became a crucial pillar of Kerala’s economy, with foreign remittances rising sharply from the early 1980s onward. By the mid-1990s, remittances accounted for around 11 percent of the state’s domestic product, increasing to over 20 percent in the following decade. These inflows transformed household incomes, spurred consumption, and elevated living standards across Kerala. Overall, the fourth wave established Kerala as a major international migration hub and set the stage for continued global engagement in the decades that followed.

The fifth wave of migration from Kerala, which began in the 1980s, was characterized by its diversity and the emergence of three distinct streams, each reflecting broader global trends and Kerala’s evolving socio-economic landscape.

The first and most prominent stream involved a continued and substantial migration of professionals, semi-skilled, and unskilled laborers to the Gulf countries. Building on the momentum of the previous wave, this period saw even larger numbers of Keralites seeking employment in the Gulf, driven by ongoing opportunities in construction, infrastructure, healthcare, and service sectors. This migration was not limited to men; increasing numbers of women, particularly in the healthcare sector, also found opportunities abroad. The remittances sent home by these migrants became a vital component of Kerala’s economy, fueling consumption, investment in housing, and improvements in education and healthcare.

The second stream was marked by the migration of highly qualified professionals—including engineers, doctors, IT experts, and academics—to a wider array of destinations beyond the Gulf. African countries such as Nigeria, Tanzania, Ethiopia, Botswana, and South Africa became significant recipients of Kerala’s skilled workforce, as did Europe, the United States, and other parts of the world. Many in this group left secure jobs in India or took leaves of absence to pursue more lucrative or professionally rewarding opportunities abroad. Their expertise was often in high demand, and their presence contributed to the development of critical sectors such as healthcare, education, and technology in their host countries. This stream also reflected the increasing globalization of the labor market and the growing reputation of Kerala’s educational and professional training systems.

The third stream was a direct consequence of the earlier migration of nurses during the fourth wave. As these nurses settled in the US and Europe, they began to bring their families over, leading to a steady increase in family-based emigration to the United States. This process, often facilitated by family reunification policies and the establishment of strong Malayali communities abroad, contributed to the creation of vibrant diaspora networks. These networks provided support for new migrants, helped preserve Kerala’s cultural identity, and facilitated further migration.

The Kerala Migration Survey (KMS) 2023 provides a comprehensive assessment of the scale and impact of migration from Kerala. According to the survey, the Loka Kerala Sabha (LKS)—a platform representing the global Kerala diaspora—estimates that there are approximately 13.3 million migrants of Kerala origin worldwide. This figure includes both international and domestic migrants and highlights the extraordinary scale of migration from this small Indian state. They constitute about 38% of Kerala’s total population, which means nearly one in three Keralites is a migrant or part of a migrant family

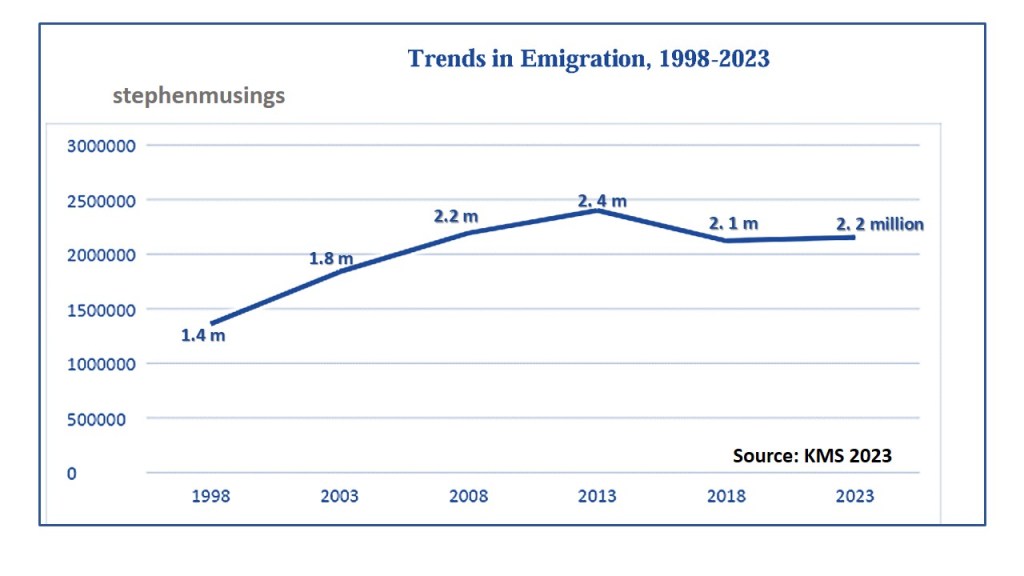

The Kerala Migration Survey (KMS), conducted every five years since 1998, has consistently documented a steady increase in the number of emigrants from the state. The KMS cycle also captures the recent moderation of migration flows.

The five waves of migration from Kerala have left a profound and lasting impact on the state, shaping its society, economy, and culture in multifaceted ways.

Socially, positive impact include the first generation of migrants establishing a strong foothold both at home and abroad. Their frequent visits to Kerala helped maintain deep bonds with their families and the larger joint family networks they left behind. On the negative front, many families experience emotional strain due to long-term separation. Spouses left behind, often women, face increased responsibilities and loneliness. Children may lack parental guidance, affecting their social development. Grandparents are left to look after themselves.

Economically, the regular remittances sent by migrants earned Kerala the nickname of a “money order economy.” The steady flow of funds from abroad not only supported families but also triggered a spending boom across the state. These remittances became a crucial pillar of Kerala’s economy, uplifting household incomes and driving local development. Total remittances from migration also reached a record ₹2,16,893 crore in 2023 from ₹85,092 crore in 2018, marking a 154.9% increase, strengthening the economy of the State. Kerala also holds a steady 21% share of India’s NRI deposits, a figure that has remained consistent since 2019.

Kerala Migration Survey (KMS) 2023 data shows that foreign remittances now account for 23.2% of Kerala’s Net State Domestic Product (NSDP), up from 13.5% in 2018. This means nearly one-fourth of the state’s economic output is directly linked to money sent home by Keralites working abroad. In 2023. In 2023, remittances were 1.7 times greater than the state’s total revenue receipts, highlighting their outsized influence on public finances and spending capacity.

The flow of foreign earnings has inflated local real estate prices, widened income disparities, and led to consumption-driven, rather than production-based, development.

Marketing and consumer habits in Kerala were also transformed by migration. Emigrants returning from abroad introduced a variety of foreign goods—such as cigarettes, liquor, perfumes, branded clothing, processed foods, and crockery—either as gifts or for sale in informal markets. These new products broadened consumer choices and influenced local tastes and lifestyles. Emigrants no longer need to bring foreign goods back with them, as these products are now readily available locally. However, their influence has significantly increased the demand for such premium goods in our region.

Culturally, migrants brought back new behaviors, customs, and culinary practices, influencing the lifestyle and eating habits of those residing in Kerala. The question is has the exposure to global cultures enriched Kerala’s own traditions in a positive way and contributed to its cosmopolitan outlook.

Kerala’s demographic landscape is being fundamentally altered by emigration, resulting in an aging population, declining fertility, and a growing reliance on migrant labor. These changes pose significant challenges for the state’s future workforce, social cohesion, and economic stability.

Religion also saw significant changes. Christian migrants established churches wherever they settled, contributing to the growth of church hierarchies abroad. Similarly, prominent Hindu temples were constructed in foreign countries, serving as centers of community and cultural identity.

Education played a pivotal role in Kerala’s migration story. Initially, ITIs and nursing schools trained Keralites for global jobs, but over time, arts and science colleges, engineering schools, and medical colleges also gained international recognition. The success of graduates in the global job market, supported by vibrant alumni associations abroad, enhanced the reputation of Kerala’s educational institutions. Before the onset of the sixth wave, as an educator, it was a source of pride to see former students excel alongside peers from prestigious Indian and international universities.

While earlier waves of emigration from Kerala were primarily driven by the search for employment and better economic prospects, the prevailing opinion on education as a motive for migration underwent a dramatic shift with the emergence of the sixth wave—student emigration. Traditionally, education was seen as a means to secure local opportunities or to prepare for jobs abroad, but not necessarily as the primary reason for leaving the country. However, in recent years, a significant and growing number of young Keralites are choosing to migrate specifically for higher education and specialized training abroad.

This new trend marks a distinct departure from previous emigration patterns. Student emigration is not just about about accessing world-class educational institutions but seeking jobs; it’s about much more.

Therefore, a comprehensive examination of the sixth wave of emigration will be reserved for an exclusive blog post.

AWAIT: THE SIXTH WAVE- KERALA EMIGRATION CHRONICLE- PART 2

Leave a comment